April 2019 NBER Digest

Fracking Disclosures by Firms Spur Productivity, Slow Innovation

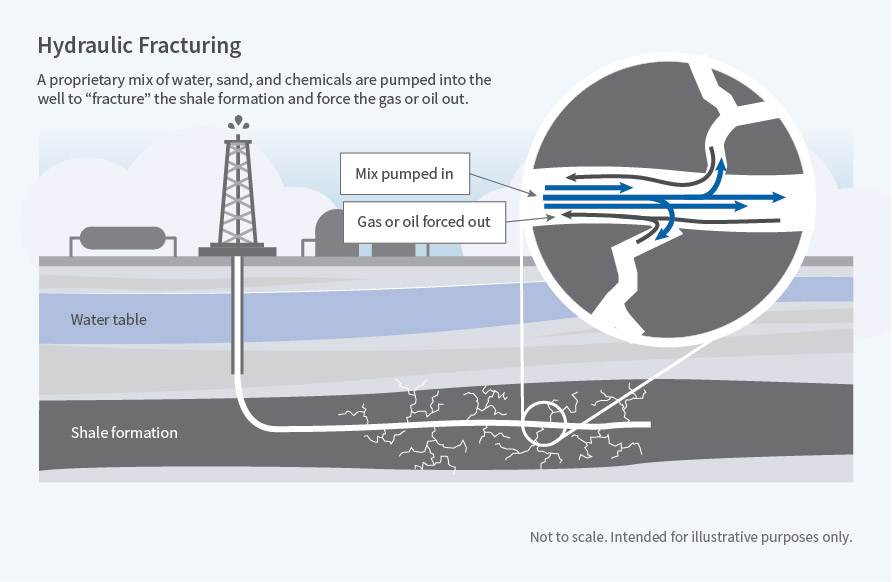

Mandatory disclosure of chemicals in fracking fluids allows competitors to catch up to industry leaders but depresses experimentation at high-productivity firms.

In many different regulatory contexts — investing, data privacy, and public health, for example — regulators rely on mandatory disclosure rules to protect consumers. These policies are seen as a way of encouraging self-regulation. In Learning by Viewing? Social Learning, Regulatory Disclosure, and Firm Productivity in Shale Gas (NBER Working Paper No. 25401), T. Robert Fetter, Andrew L. Steck, Christopher Timmins, and Douglas Wrenn study whether these regulations affect knowledge transmission and firms' incentives to innovate in the hydraulic fracturing industry, which has been a recent focus of regulation.

Explaining Why Investors Hold Sovereign Bonds with Default Risk

Repeating 8th Grade Increases Likelihood of a Criminal Conviction

Sherman's March Left a Lasting Legacy of Retarded Development

Women from Elite Colleges Earn More Because They Work More

New Estimates of the Benefits of U.S. Highway Construction

Fracking Disclosures by Firms Spur Productivity, Slow Innovation

< Previous Digest Issues >

In the face of concerns about the chemicals used in the hydraulic fracking process, 18 U.S. states have instituted public disclosure rules since 2010. Using a dataset on well-level chemical inputs and production in Pennsylvania, the researchers explore the consequences of that state's disclosure regulations.

They first analyze whether the disclosure regulations resulted in cross-firm learning. They find that firms modify the chemicals they used in their fracturing fluids based on the disclosures of other firms, documenting a "...convergence in the chemicals used consistent with copying from disclosed wells." Not surprisingly, the fracturing fluid experiments that are the most likely to be copied are those conducted by the most productive firms. This finding suggests that "the disclosure laws helped to facilitate the diffusion of innovation conducted by the most productive firms."

The researchers next show that the disclosed chemical formulas had economic value to the firms that copied them. The well operators who copied the chemical formulas of more productive firms enjoyed higher productivity than comparable operators who did not.

The near-term gains in productivity as a result of cross-firm learning could be counterbalanced in part by another effect of the disclosure rules: Innovative firms may have less incentive to innovate, since they know that their valuable advances will be copied by other firms. The researchers find a reduction in innovation after the implementation of disclosure requirements in Pennsylvania. This effect is particularly notable for operators in the top quartile of the productivity distribution. In the pre-regulation period, 15 percent of wells at high-productivity firms used experimental chemical combinations; in the post-regulation period, only 5.7 percent did.

— Dwyer Gunn

The Digest is not copyrighted and may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution of source.