NBER Reporter 2010 Number 1: Research Summary

The Credit Rating Crisis

Efraim Benmelech *

The credit crisis of 2008-9 was in many ways a credit rating crisis. Structured finance products, such as mortgage-backed securities, accounted for over $11 trillion dollars worth of outstanding U.S. debt. The lion's share of these securities were highly rated -- for example, more than half of the structured finance securities rated by Moody's carried a AAA rating, the highest possible credit rating that is typically reserved for securities deemed to be nearly riskless. In 2007 and 2008, the creditworthiness of structured finance securities deteriorated dramatically: 36,346 Moody's rated tranches -- tranches are a class of security with a prioritized claim against the collateral pool -- were downgraded, and nearly one third of the downgraded tranches bore the AAA rating. In November 2007 alone, there were 2,000 downgrades and many were severe: 500 tranches were downgraded more than 10 notches. The ensuing confusion about the true value of these complicated securities, and the extent of exposure by financial institutions, incited a credit crunch with effects beyond subprime mortgage-related investments.

The Role of Credit Ratings in the Process of Securitization

Securitization is a broad term that encompasses several kinds of structures by which loans, mortgages, or other debt instruments are packaged into securities. The essence of securitization is pooling and tranching. After pooling a set of assets, the issuer creates several different classes of securities, known as tranches, with prioritized claims against the collateral pool. In a tranched deal, some investors hold more senior claims than others. In the event of default, the losses are absorbed by the lowest priority class of investors before the higher priority investors are affected. Naturally, the process of pooling and tranching creates some securities that are riskier than the average asset in the collateral pool and some that are safer.

The structured finance market is a "rated" market - the vast majority of securities issued are rated by at least one rating agency. Given the complexity of the underlying collateral and the asymmetric information between issuers of these securities and investors, credit ratings serve as a focal point for the quality of the securities.

The interaction between credit ratings and financial regulation was an important driver of growth in securitization markets. The extensive use of credit ratings in the regulation of financial institutions created a natural clientele for highly rated - and in particular AAA-rated - securities. Minimum capital requirements at banks, insurance companies, and broker-dealers, depend on the credit ratings of the assets on their balance sheets. Pension funds also face rating-based investment restrictions. The process of securitization enabled these investors to participate in asset classes from which they would normally be prohibited. For example, an investor required to hold investment-grade securities could not directly invest in B-rated corporate loans but could invest in a AAA-rated CLO security backed by a pool of B-rated corporate loans. Structured finance securities typically yield a higher interest rate than similarly rated corporate or sovereign bonds, making them an attractive investment for rating-constrained investors.

The Collapse of Credit Ratings during the Crisis

Jennifer Dlugosz and I examine the rating performance of all structured finance securities issued in the period 1990-2008.1 We show that the deterioration in the creditworthiness of structured finance products began in 2007. There were more than 8,000 downgrades in 2007 - an eightfold increase over the previous year. In the first three quarters of 2008, there were 36,880 downgrades, overshadowing the cumulative number of downgrades since 1990. Downgrades were not only more common in 2007 and 2008 but also more severe. The average downgrade was 4.7 notches in 2007 and 5.8 notches in 2008, compared to 2.5 notches in both 2005 and 2006. Meanwhile, upgrades were less frequent and smaller in magnitude on average.

Figure 1Many of the downgrades in 2007 and 2008 were tied to collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) backed by assets that are themselves structured (ABS CDOs). While initially ABS CDOs were diversified and collateralized by assets from a variety of sectors, they became more concentrated over time. Since 2003 the primary asset classes backing them were subprime and non-conforming residential mortgage-backed securities. Many of these ABS CDOs were downgraded during the crisis, leading to large selloffs of these securities and losses at financial institutions. Dlugosz and I show that in early 2009, financial institutions around the world wrote down more than half a trillion dollars, out of which more than 200 billion dollars resulted from exposure to ABS CDOs that were severely downgraded.

Why Did the Ratings Collapse?

What led to the collapse of structured finance credit ratings? Were the initial credit ratings assigned to securitized bonds too high? Or was it the unforeseen economic downturn and nationwide decline in the housing market that led to the deterioration in credit quality of these securities? Put differently, did the credit rating agencies make honest mistakes in estimating default risk, or did they assign inflated credit ratings to risky securities?

A. Rating Shopping

Rating shopping occurs when an issuer chooses the rating agency that will assign the highest rating or that has the most lax criteria for obtaining a desired rating. Most rating agencies operate under an issuer-pays revenue model where issuers solicit and pay for their own bond ratings. If reputational concerns are not strong enough to discipline rating agencies, the issuer-pays model can result in inflated ratings. Rating shopping concerns are particularly pronounced for structured finance bonds - as opposed to corporate or municipal bonds - because of the lack of public information on these securities. Recent research has developed models in which rating agencies trade-off the value from inflating its client's rating against an expected reputation cost.2 However there is little empirical evidence testing the rating shopping hypothesis.

Dlugosz and I test whether "rating shopping" led to inflated ratings of ABS CDOs. We examine whether the number of agencies that rate a security can predict the probability of subsequent downgrades. Structured finance tranches are rated by Moody's and S&P, and to a lesser degree by Fitch, hence the number of raters can range from 0 to 3. We find that the probability that the tranche will be downgraded within a year after issuance is higher for tranches rated by only one rating agency. Moreover, tranches rated by only one agency are not only more likely to be downgraded but also experience more severe drops in creditworthiness when compared to tranches that are rated by more than one agency. Our results also provide suggestive evidence that the rating model used by S&P may have been inflated and that rating shopping may have played a role in the collapse of the structured finance market. Industry experts questioned the S&P rating model and some of its underlying assumptions. For example, on December 19, 2005, S&P put 35 tranches from 18 different deals on negative watch following an update of its rating criteria. Out of the 18 deals, 14 carried ratings only from S&P - suggesting that the issuers involved in these deals may have "shopped" for their rating.

B. Rating Alchemy and the Failure of the Black Box

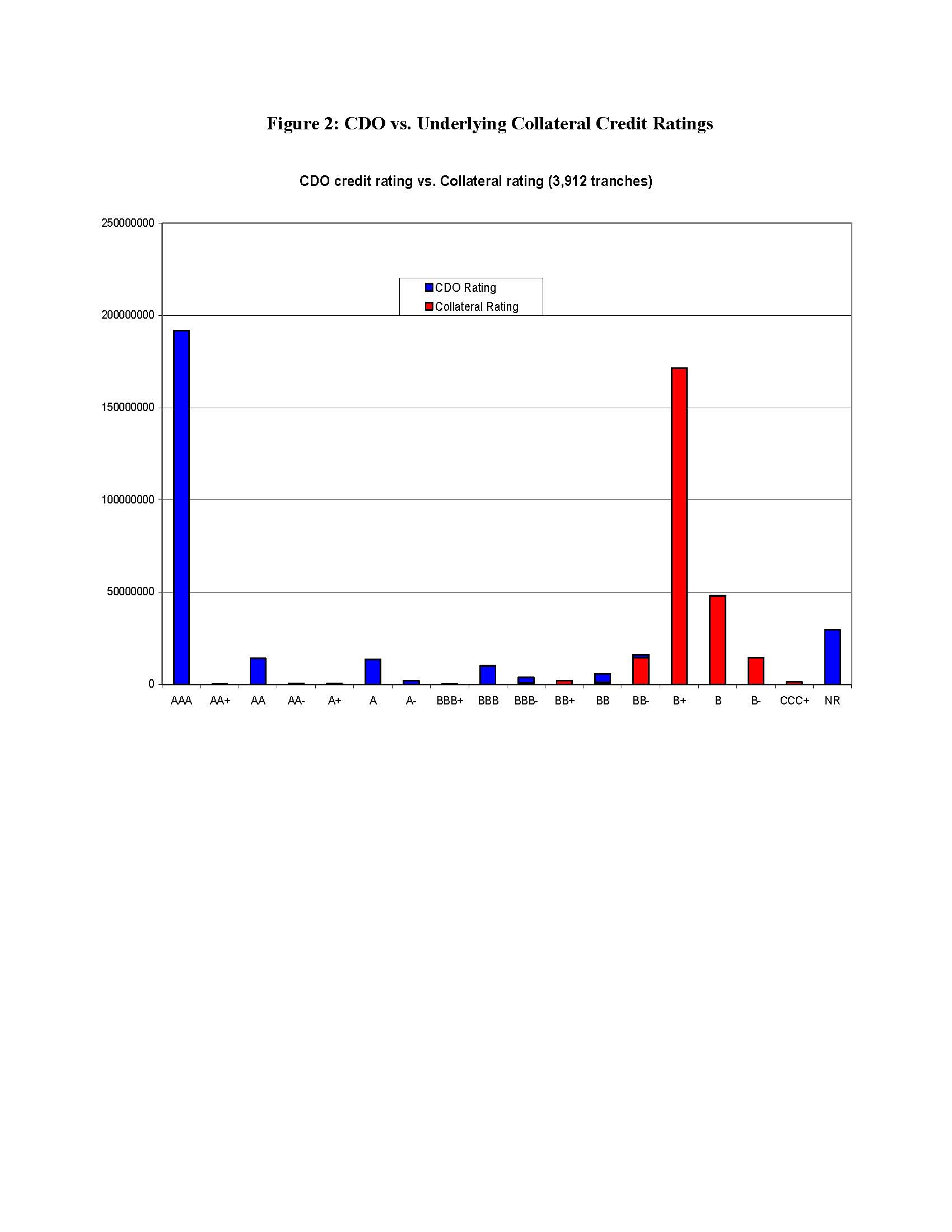

In "The Alchemy of CDO Credit Rating," Dlugosz and I study the underlying collateral of CDOs secured by corporate loans.3 We find a striking difference between the credit rating structure of the CDO and the credit quality of the collateral pool.

Figure 2

Figure 2

While the average credit quality of the loans being securitized is around B, more than 70 percent of the dollar amount of CDOs was initially rated as AAA. For this mismatch to be appropriate, it would need to be the case that a pool of assets with an average credit quality of B be able to withstand enough losses such that 70 percent of its liabilities will still remain default-risk free.

We also document a large degree of uniformity in CDO structures. The CDOs that we study have very similar liability structures and very similar collateral pools. There is little variation in the quality of the underlying collateral across different issuers; while we study around 4,000 tranches they all seem to conform to the same CDO model. What caused the uniformity in CDO structures?

One potential answer is that CDO issuers just follow market convention: if some CDO structures have been perceived as desirable, then other issuers will follow the same convention. However, while this would explain the uniformity in deal structures (that is, the amount allocated to each category), what explains the uniformity of the underlying collateral? An alternative explanation is that the issuers had access to the rating model of the credit rating agencies. According to this explanation, the rating agencies provided issuers with their model, and issuers structured their CDOs accordingly.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the rating agencies models indeed were known to CDO issuers and were provided to them directly by the rating agencies. For example, the CDO Evaluator Manual - an optimization tool used by S&P - enabled issuers to achieve the highest possible rating at the lowest possible cost. The model, for example, would indicate to issuers when they had "excess collateral" and would advise issuers on: "the percentage of assets notional needs to be eliminated (added) in order for the transaction to provide just enough support at a given rating level."

Thus, the rating agencies may have served not just as monitors and evaluators of existing structures, but rather as architects and creators of new securities. Providing such models to issuers potentially led to the creation of CDOs with the minimum possible collateral needed to obtain an AAA credit rating. The uniformity across CDOs and the low credit ratings of the underlying collateral suggest that most issuers were using the model to target the highest possible credit rating at the lowest cost. If there were mistakes embedded in these credit rating black boxes - those were probably compounded over the trillions of dollars that were deliberately structured by CDO issuers using this model.

* Benmelech is a Faculty Research Fellow in the NBER's Program on Corporate Finance and Development of the American Economy and is an associate professor of economics at Harvard University. His profile appears later in this issue.

1. E. Benmelech and J. Dlugosz, "The Credit Rating Crisis," NBER Working Paper No. 15045, June 2009, and NBER Macro Annual, 2009, forthcoming.

2. P. Bolton, X. Freixas, and J. Shapiro, "The Credit Ratings Game," NBER Working Paper No. 14712, February 2009. E. Damiano, H. Li, and W. Suen, "Credible Ratings," Theoretical Economics, 3 (September 2008), pp. 325-65. F. Sangiorgi, J. Sokobin, and C. Spatt, "Credit Ratings Shopping, Selection and the Equilibrium Structure of Ratings," Working Paper, November 2008.

3. E. Benmelech and J. Dlugosz, "The Alchemy of CDO Credit Ratings," NBER Working Paper No. 14878, April 2009, and Journal of Monetary Economics, 56(5) (July 2009), pp. 617-34.