May 2017 NBER Digest

Early Evidence on the Effects of the ACA

The Affordable Care Act has reduced the percentage of uninsured Americans by 44 percent, but whether it has had positive health effects remains unclear.

Increased access to affordable health care does not necessarily translate to a decrease in smoking, substance abuse, or obesity, or to better self-reported health. Those are among the principal findings of Early Effects of the Affordable Care Act on Health Care Access, Risky Health Behaviors, and Self-Assessed Health (NBER Working Paper No. 23269), by Charles Courtemanche, James Marton, Benjamin Ukert, Aaron Yelowitz, and Daniela Zapata.

Robots and Jobs in the U.S. Labor Market

Early Evidence on the Effects of the ACA

Exploring Pathways to Economic Development

The Global Rise of Corporate Saving

Patent Awards Stoke Startup Growth

Marriageability Concerns and Professional Ambitions

< Previous Digest Issues >

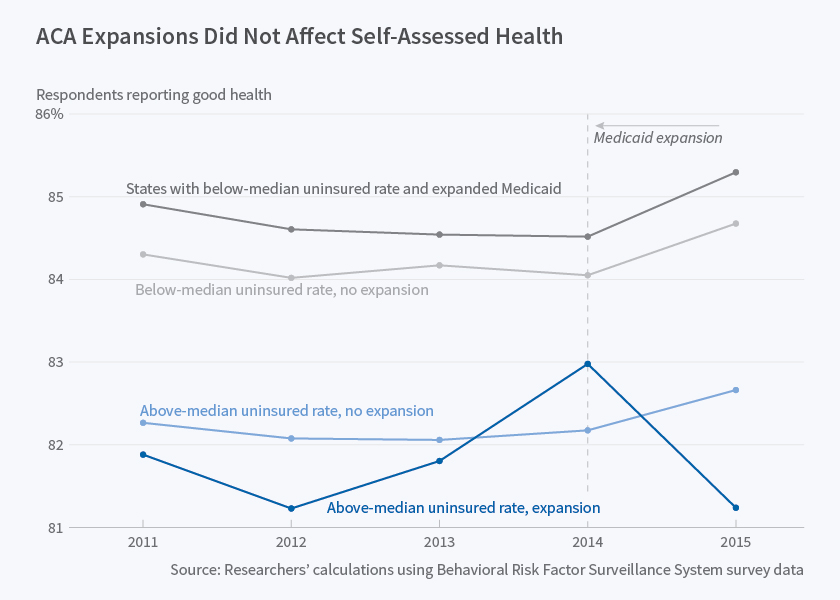

The researchers analyze data spanning the years 2011 to 2015 from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an annual nationwide telephone survey conducted by state health departments. They focus on adults aged 19 to 64. The survey records responses from more than 300,000 individuals each year.

The researchers compare responses before and after the Affordable Care Act (ACA) took effect. They also compare survey results in states that fully adopted the ACA, embracing extended Medicaid coverage, with those that did not. They estimate that, when fully adopted, the ACA reduced the number of uninsured individuals by 44 percent, while also reducing the number without a primary care doctor by 12 percent. The number of respondents who reported that they had foregone care because of cost dropped by 28 percent, and the number who had not had an annual health checkup declined by 10 percent.

Despite these improvements in health care access, the researchers find no statistically significant differences in risky behaviors and self-assessed health status between respondents in pre- and post-ACA surveys. That is the case both in states that expanded Medicaid and in those that did not. When they disaggregate their findings and consider smaller age groups, the researchers report some evidence that the ACA improved self-assessed health among older, non-elderly adults, particularly in Medicaid expansion states.

The researchers suggest that health literacy may lag behind health access, so it may take time before the newly insured find suitable care givers, modify their health-related behaviors, and follow through on treatment plans. As support for this view, they note that, in those states where the ACA was fully implemented, insurance coverage increased by 8.3 percentage points, but the probability of having a checkup rose by less than half that: 3.6 percentage points. The researchers also note that with better access to health care, some individuals may be less concerned about the financial consequences of poor health, and consequently devote less attention to healthy behaviors.

The researchers caution that their findings offer only a partial picture of the ACA's impact. They do not, for example, capture the effect of expanded coverage on clinical outcomes such as the treatment of diabetes or asthma, except insofar as such treatments might affect self-reported health.

"Improved access to medical care may be of only limited value with regard to health behaviors since they are generally not as easy to treat as acute conditions," the researchers write, adding that the impact on self-assessed health may take longer than two years to register. They also point to the importance of studying financial as well as physical health. "[P]rotection against financial risk is a critical component of the gains from insurance, so the consumption smoothing benefits of the ACA could confer a sizable benefit even in the absence of discernable short-run health effects."

— Steve Maas

The Digest is not copyrighted and may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution of source.