The Insurance and Liquidity Value

of Social Security Survivors Benefits

The death of a spouse is not only an emotional loss but often a considerable financial loss as well, as the surviving spouse can no longer rely on the deceased spouse's earnings or retirement benefits. Social Security survivors benefits help to protect against this loss of income by paying benefits to the surviving spouse of an eligible deceased worker if he or she is caring for children (under age 16) or is age 60 or above. In 2015, the Social Security program paid over $95 billion in survivors benefits to 4.2 million surviving spouses. Almost all of these beneficiaries are women (98 percent in 2017), since women live longer than men and many older widowers receive their own (larger) retired worker benefit instead of a survivors benefit.

Despite the potential importance of survivors benefits to the well-being of widows, their effect has not been extensively studied. A recent paper by researchers

Itzik Fadlon,

Shanthi Ramnath, and

Patricia Tong, Market Inefficiency and Household Labor Supply: Evidence from Social Security's Survivors Benefits (NBER Working Paper 25586) aims to help fill this gap.

The authors exploit the fact that survivors benefits are available to widows (other than those caring for children) starting at age 60, enabling them to compare the experiences of women whose husband's death occurs just before and after the age eligibility cutoff. Using tax records for the U.S. population for the years 1999 to 2014, the authors compile a panel data set of nearly a quarter of a million women who experience a husbands' death. These data allow them to explore various financial outcomes and behaviors both immediately following the spouse's death and in the longer run. The authors put emphasis on widows' labor supply responses that they show are informative in identifying market efficiency, since households who have access to perfect markets should be able to smooth their behavior across eligibility statuses.

The authors first explore the protective insurance role of survivors benefit receipt against the immediate adverse financial consequences of a spousal death. Relative to those widowed before age 60, widows who are just eligible for benefits upon their husband's death are about 50 percentage points more likely to be receiving Social Security benefits, with an average increase in annual Social Security income of about $5600 (indicating an effect about twice this size for those who claim benefits). The effect on total household income, which accounts for adjustments in alternative sources such as private savings and other government transfers, is only slightly smaller – eligibility is associated with an increase in income of about $4,800, an 11.4% increase. The authors also examine the labor supply effects of survivors benefits. Relative to slightly younger widows, widows eligible for benefits are 2.9 percentage points less likely to be in the labor force and experience a decline in average annual earnings of about $1,750. As the authors highlight, these labor supply responses in the immediate post-shock periods reveal considerable allocative inefficiencies in the life insurance market. The authors find even stronger effects among low-earning widows, who experience a 20.1% increase in income and a 27% decrease in labor earnings.

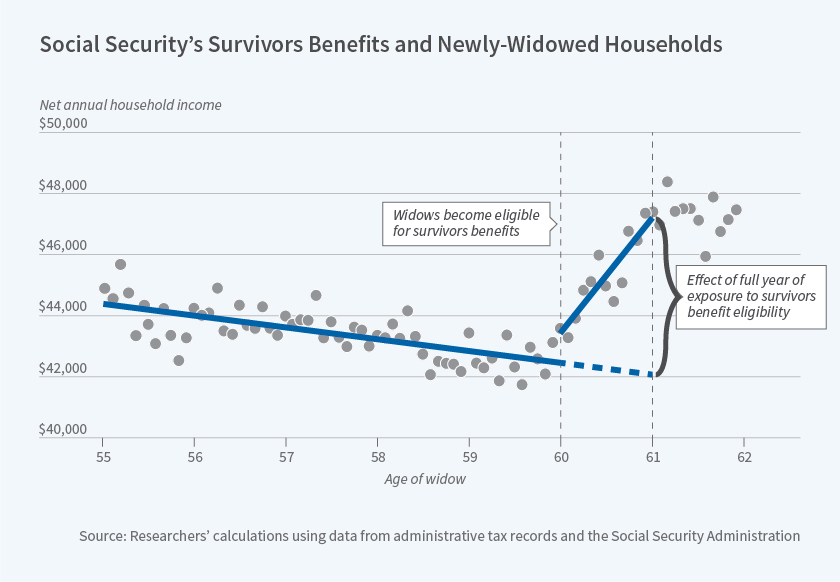

Next, to explore the value of liquidity provided by government transfers, the authors conduct a second analysis in which they estimate the effect of reaching the age of eligibility for survivors benefits for already-widowed households. They find that attaining benefit eligibility is associated with a 34-percentage point increase in Social Security receipt and an average increase in Social Security income of about $3,650. Reaching benefits eligibility is also associated with a 3.1-point decline in labor force participation and a decline in annual labor earnings of about $1,900. This meaningful reduction in labor supply in response to a predictable increase in cash-on-hand at the benefits eligibility age "indicates considerable allocative inefficiencies in credit and liquidity among U.S. households." The authors provide several tests which point to liquidity constraints, rather than benefit misperception or myopia, as the likely mechanism that underlies these responses to anticipated benefits.

Overall, the results suggest that survivors benefits have important impacts on the behavior and financial security of American families. As the authors note, "the evidence points to significant protection the program provides against the immediate adverse economic impacts of spousal mortality, which comes in the form of considerable increases in net household income and in the consumption of leisure by widowed households. What is more, the evidence underscores the importance of liquidity provided to widowed households by the federal government, both in terms of its insurance role of smoothing consumption across states of nature and in terms of its intertemporal role of smoothing consumption over time... With these conclusions, our analysis further suggests potentially important gains from providing coverage to ineligible families and from a smoother benefit profile."

This research was supported by the U.S. Social Security Administration through grant #RRC08098400-09 to the National Bureau of Economic Research as part of the SSA Retirement Research Consortium.